I have talked about achieving mastery previously. Here's another, perhaps better researched article on how long it takes to achieve mastery of a discipline. For those too indolent to click a link, what it says is that it takes about 10,000 hours, or about five full-time years, to obtain a reasonable degree of mastery, and it doesn't matter what it is; playing the violin, swinging a baseball bat, or coding in C++. A study of violinists indicated that "natural" talent was not a factor. The people who were the best were the ones who practiced the most and the longest.

This is something recent college grads all seem not to know about the careers on which they are embarking. They think (like I once thought) that their natural intelligence and their good education was what made the difference. As an Old Hand, I can tell you that practice has a lot to do with it, and good as you are, you will get a lot better when you've been doing the job for 20 years.

Showing posts with label lesson. Show all posts

Showing posts with label lesson. Show all posts

Friday, December 4, 2015

Monday, March 30, 2015

Aphorisms for Work

Here are some aphorisms that I think upon, usually during meetings with grumpy managers.

It takes the same time to do a project right as to do it wrong

You just spend the tine in different places. You can rush through coding without any planning, but you will spend a lot of time in front of the debugger, and maybe have to throw your code away and start over when you understand the problem better. Or you can do thoughtful design, code at a deliberate pace, run your unit tests, and be done. It comes down to a lifestyle choice.

The most dangerous thing in the world is a half-understood Harvard Business Review article

There's an HBR article that says, essentially, "All other things being equal, getting software done sooner results in greater revenue." This one paper is the cause of so much misery for development teams. Managers love to use this article as an excuse to pry the software out of development and jam it into production before it's finished. They never read the "all other things being equal" part of the article.

There is an HBR article that says, "Pay is not what motivates employees the most." There are managers who read this article and think they can overwork and underpay their employees. They don't read the part about what does motivate employees, like empowerment, recognition, and work/life balance.

The most pain is inflicted when the manager hears a summary second-hand, and doesn't even know he has only half the advice. He thinks, "There's an HRB article that says you should ship the project as early as possible", or "HBR says employees don't care that much about pay."

When everything is important, nothing is

Ever have your manager tell you on Monday to work on this, because it is the most important thing, and then tell you on Tuesday to work on that, because it is the most important thing. And then you ask him to choose which is most important, and he says they both are? That is what a weak manager does when he doesn't want to make a decision. There must be a most important thing, the thing to finish first.

If everything is important, if everything is an emergency, then nothing is really important, because your manager will blame you for what you didn't choose, no matter what you did choose. If your manager behaves in this way, it's a good time to get your resume updated and start looking for work.

The 90/90 Rule: The first 90% of development takes 90% of the time, and the last 10% takes the other 90% of the time

Oh, how many times has a developer said he was 90% done in one month, only to spend a second month on that last pesky ten percent? You're 90 percent done with the part of the task you know about. Generally that's about half the task. It's a very mature organization indeed that can correctly estimate completion percentages. Your best chance is to estimate things using a consistent process, and then consistently record how your estimate matched reality. Then you can de-rate future estimates until your estimation process matures.

It takes the same time to do a project right as to do it wrong

You just spend the tine in different places. You can rush through coding without any planning, but you will spend a lot of time in front of the debugger, and maybe have to throw your code away and start over when you understand the problem better. Or you can do thoughtful design, code at a deliberate pace, run your unit tests, and be done. It comes down to a lifestyle choice.

The most dangerous thing in the world is a half-understood Harvard Business Review article

There's an HBR article that says, essentially, "All other things being equal, getting software done sooner results in greater revenue." This one paper is the cause of so much misery for development teams. Managers love to use this article as an excuse to pry the software out of development and jam it into production before it's finished. They never read the "all other things being equal" part of the article.

There is an HBR article that says, "Pay is not what motivates employees the most." There are managers who read this article and think they can overwork and underpay their employees. They don't read the part about what does motivate employees, like empowerment, recognition, and work/life balance.

The most pain is inflicted when the manager hears a summary second-hand, and doesn't even know he has only half the advice. He thinks, "There's an HRB article that says you should ship the project as early as possible", or "HBR says employees don't care that much about pay."

When everything is important, nothing is

Ever have your manager tell you on Monday to work on this, because it is the most important thing, and then tell you on Tuesday to work on that, because it is the most important thing. And then you ask him to choose which is most important, and he says they both are? That is what a weak manager does when he doesn't want to make a decision. There must be a most important thing, the thing to finish first.

If everything is important, if everything is an emergency, then nothing is really important, because your manager will blame you for what you didn't choose, no matter what you did choose. If your manager behaves in this way, it's a good time to get your resume updated and start looking for work.

The 90/90 Rule: The first 90% of development takes 90% of the time, and the last 10% takes the other 90% of the time

Oh, how many times has a developer said he was 90% done in one month, only to spend a second month on that last pesky ten percent? You're 90 percent done with the part of the task you know about. Generally that's about half the task. It's a very mature organization indeed that can correctly estimate completion percentages. Your best chance is to estimate things using a consistent process, and then consistently record how your estimate matched reality. Then you can de-rate future estimates until your estimation process matures.

Tuesday, April 1, 2014

We're Special -- a Conversational Anti-Pattern

I've worked within organizations that

told themselves that some best practice widely promoted throughout

the industry cannot possibly be applied at this organization, because

this organization's work is "special". Our code isn't like

other code. Our customers aren't like other customers. Our problems

aren't like other companies problems, so this commonsense rule does

not apply to us (and therefore we need not change our practice).

When I had the evangelical furvor of the rookie, this behavior made me wild. It was clear to me that there was absolutely nothing special about our code, and that industry best practices got to be best practices exactly because they were widely applicable. I came to understand that the purpose of the word "special"

in this conversation was to defeat any kind of reasoned argument, any

comparison or evidence, and defend the status quo.

When I became an old hand (and by that I mean, as I was typing this blog entry after facing this anti-pattern yet again), I realized something else. I realized that "special" was the antidote to the phrase "best

practice", which itself is meant to defeat argument without presenting evidence.

When you find yourself in such a

conversation, it means that both sides have staked out a position

that they are too lazy to defend with any actual evidence. To make

any progress you must change the conversation. Perhaps, "Best

practice X will improve our results in thus-and-such a way.", or, "Practice P is being used successfully by our own competitors."

This raises the level of the conversation so that the other

stakeholders must argue specifically against your evidence.

When they say "special", you can then say, "Yes, but

in what way does our special-ness invalidate the evidence?"

It is tedious to argue from evidence, and

easy to resort to words like "special" and "best

practice". However, the comversation generally goes better if you come prepared with some actual data.

Thursday, March 6, 2014

Things Only Taught by Time

What do you learn over a career of coding, besides 123 different APIs? What's all this value in being an Old Hand? Well...

- When I was interviewing for work, right out of college, there was a job I didn't take because all the developers had foot-thick listings on top of their filing cabinets. I knew my modest brain could never comprehend such a massive amount of code. Ten years later, I delayed learning Windows programming because applications appeared indecipherably complex, with dlls and a configuration database instead of a single executable.

I don't print paper listings any longer, but if I did, mine would be ten feet tall. I've built many Windows apps. It sucks to manage dlls, but not because they're too complex to comprehend.

LESSON: Anything that other programmers are comfortable with is not too complex for you.

- I spent 10 years becoming a deep domain expert at my first company out of college. I figured I would become a "lifer", safe from the travails of the job market because of my valuable knowledge. Then during an economic downturn, the company changed strategic direction. They shuttered my whole division, laying me off along with 19 of 21 engineers, 12 of 12 marketing folks, and about 50 factory workers.

It was hard finding a new job because (1) it was the bottom of a recession, (2) my deep domain knowledge was not applicable at any other employer in the city, and (3) I had neglected to learn the latest programming skills because I didn't believe, as a lifer, that I would need them to be up-to-date.

LESSON: Skills and experience are only valuable if they help you find work.

LESSON: Skills and experience that help you find work are valuable.

- The two engineers that my one-time lifetime employer retained? One was a very lucky new college hire. The company valued its reputation for firm job offers. The other survivor was a nice lady; very quiet, someone who never asked questions or made requests. She wasn't the smartest engineer. She wasn't the most innovative. But she turned out an utterly reliable so-many-lines of code each month without variation. She became a lifer at that company.

LESSON: what managers value in a software developer is not intelligence, or innovation, or great code. They value reliably low maintenance workers.

- My very favorite sister-in-law died of cancer at 39 years of age. When her cancer was diagnosed, she didn't quit her job right away, but she did change her behavior. All of a sudden there were some meetings and some tasks that seemed so unnecessary that they offended her sense of limited remaining time. She told me that a week before her diagnosis, she had wasted a bunch of time in these meetings, and all of a sudden she really wanted that time back. She began focusing exclusively on the parts of her job that added value and that gave her satisfaction. She put off the dumb stuff as long as she could. She discovered that lots of dumb stuff eventually just went away if she put it off, because it was dumb stuff. She didn't lose touch by skipping boring meetings. They were boring because nothing happened in them. In this way she became recognized by her managers as the most productive worker in her office.

I was going to boring meetings where nothing happened too. I vowed to behave as though I had six months to live. I became more productive, because I only did activities that added real value, and that I enjoyed. I came to feel as though I had become bulletproof. I reasoned that if I was ever let go for only doing productive work, the company would be doing me a tremendous favor. Such a company would not last long, and working there until the end would be awful.

LESSON: Only do tasks that add value. You will be the most productive member of your team.

- I became unemployed in the dot.com crash, becaue my dot.com employer collapsed. It was hard to find work because it was the dot.com crash, and nobody was hiring. It wasn't that I had the wrong skills or wanted too much money. There just wasn't anyplace to send a resume. It turned out that I wasn't bulletproof after all. I went from being the most employable guy I knew to being chronically unemployed. I became unemployed again in the Great Recession. Two employers in a row suffered dramatic, thirty per-cent revenue declines, and laid off their whole software team.

LESSON: Bulletproof is not the same as invulnerable. Pride goeth before a fall.

LESSON: Most software development work is project-oriented. Your job is always vulnerable between projects.

LESSON: It is always the bottom of a recession when you get laid off. Nobody will be starting new projects then. It is prudent to have money in the bank to last you a year or so.

Tuesday, August 14, 2012

Resumes: The 80% Rule

I've sat on both sides of the interview table. I've been a lead looking for competent hires for a complex software project. My experience hiring staff can't be that different to the mainstream.

I'm amazed at the resumes I receive. I'm amazed at the quantity; about 100 resumes back in the day when we wrote newspaper ads. Somewhat fewer for an ad on hotjobs or monster. When I'm hiring, I don't have HR filter the candidates, because if they do, I don't get any resumes. I love the folks in HR, but they just don't know enough about software. So, 100 resumes in a pile, or 100 resumes in my in-box.

About 80 per cent of the resumes I receive are unqualified on their face for the clearly described position for which I'm hiring; retreaded poets and astronomers; guys with no experience at all in the languages or technologies I specified; people with no degree and no experience and no apparent ability to write grammatical english sentences. People whose home address is on a different continent (plus they have no experience). I guess these guys send a resume to absolutely every job posting, web site, and advertisement. They might as well not bother. These resumes go in the recycling on the first pass. (HR keeps a copy for awhile, because there is a requirement that they do so).

That leaves about 20 resumes that are worth a second look, which is to say a careful, front-to-back reading. Of these resumes, about 80 per cent are unqualified in some specific way. You can understand why they applied, but they are not the droids you are looking for. Not enough experience, not the right experience, or there's just something funny about them.

That leaves five resumes that are people you want to call up and talk to and maybe have in for an in-house interview. Of these five, there are maybe one or two (20% again) that you might make an offer to.

And there is another one who is lying to you. You bring them in for an in-house interview and their experience melts away. They clearly don't know what they're talking about. They just aren't what they say they are. Posers; fakes; cheats. And not very good ones, because you bust them in a couple of hours of interviews.

In the modern age, the barriers to submitting a resume are far lower, but there are more jobs. What that means to a hiring manager is more resumes that do not make the first cut, and fewer qualified candidates from whom to choose. You might not even get one candidate you want to hire, so your job stays open longer...and longer...and longer, while your team misses milestones because they are too few.

So, if it seems like your beautiful resume disappears into a black hole every time you submit it, remember that it's a needle in a pretty big haystack. If you get called, you made the first two cuts, the 20 per cent of the 20 per cent. That's pretty good.

I'm amazed at the resumes I receive. I'm amazed at the quantity; about 100 resumes back in the day when we wrote newspaper ads. Somewhat fewer for an ad on hotjobs or monster. When I'm hiring, I don't have HR filter the candidates, because if they do, I don't get any resumes. I love the folks in HR, but they just don't know enough about software. So, 100 resumes in a pile, or 100 resumes in my in-box.

About 80 per cent of the resumes I receive are unqualified on their face for the clearly described position for which I'm hiring; retreaded poets and astronomers; guys with no experience at all in the languages or technologies I specified; people with no degree and no experience and no apparent ability to write grammatical english sentences. People whose home address is on a different continent (plus they have no experience). I guess these guys send a resume to absolutely every job posting, web site, and advertisement. They might as well not bother. These resumes go in the recycling on the first pass. (HR keeps a copy for awhile, because there is a requirement that they do so).

That leaves about 20 resumes that are worth a second look, which is to say a careful, front-to-back reading. Of these resumes, about 80 per cent are unqualified in some specific way. You can understand why they applied, but they are not the droids you are looking for. Not enough experience, not the right experience, or there's just something funny about them.

That leaves five resumes that are people you want to call up and talk to and maybe have in for an in-house interview. Of these five, there are maybe one or two (20% again) that you might make an offer to.

And there is another one who is lying to you. You bring them in for an in-house interview and their experience melts away. They clearly don't know what they're talking about. They just aren't what they say they are. Posers; fakes; cheats. And not very good ones, because you bust them in a couple of hours of interviews.

In the modern age, the barriers to submitting a resume are far lower, but there are more jobs. What that means to a hiring manager is more resumes that do not make the first cut, and fewer qualified candidates from whom to choose. You might not even get one candidate you want to hire, so your job stays open longer...and longer...and longer, while your team misses milestones because they are too few.

So, if it seems like your beautiful resume disappears into a black hole every time you submit it, remember that it's a needle in a pretty big haystack. If you get called, you made the first two cuts, the 20 per cent of the 20 per cent. That's pretty good.

Thursday, August 9, 2012

2,000 Mondays

This post is a warning to undergrad CS majors. The stories you hear about the "real world" are not the truth.

There's this place called Xerox PARC. At the dawn of the Computer Age they invented personal computers, and Ethernet, and Smalltalk, and windows and stuff. And the conference rooms were full of beanbag chairs and the streets were paved with gold. This is what your professors think the real world looks like.

There's this cool startup you'll hear about (a different one each year), where they give you a MacBook to develop on, and there is free pop and snacks in the fridge, and wine on Fridays, and the office is decorated in twenty-something chic, with a universal gym and foosball tables, and you can work any hours you want, and dress like a slob.

This is the "real world" you hear about in college. It's a world where nerds rule and employers are so desparate for top talent that they'll do anything to keep you happy.

It's a fantasy; a fairy tale told by people (students) who have never even seen the real world, and people (professors) who turned their backs on the real world in favor of a place where you could never ever ever be fired no matter how you behaved, once you got tenure.

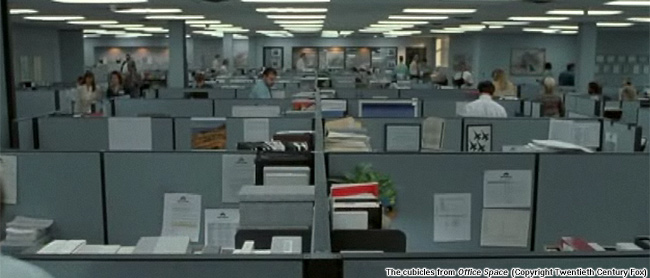

Mostly, the real world looks like this.

The real world is a very interesting place. There are lots of challenging, engaging projects in the real world. But it's not a playground. Most offices are cube farms or open bullpens. There are a whole lot of add/change/delete screens

and login pages to code for each unique and challenging algorithm you get to invent. There are a thousand lines of somebody else's poorly written code to patch for every line of your own unique software stylings.

Employers really are desparate for top talent. Only the thing is, new grads aren't top talent, no matter how smart you are. You're a n00b, a novice. You won't even know how much you don't know for a couple of years. To employers, top talent means that one guy on the team who turns out 10 times as many lines of solid, functioning code as anyone else; who works 80 hour weeks for 40 hours of pay; who's been coding since he built his first computer from individual logic gates when he was six. Top talent has already worked for Microsoft and Google and Facebook. That's how your employer knows they're top talent. You haven't worked for anyone at all.

There are indeed startups with free food, and wine, and foosball, and a fancy office. They just aren't all the same startup. And most of them are in just one or two cities; cities where a decent house costs a million bucks; cities you don't currently live in. What every startup has is long hours and low wages and stock options, which 99 times out of 100 expire worthless, and 1 percent of the time make you a millionaire. Most startups only live for a year. Then they crash and take your dreams of wealth with them, leaving you unemployed, wondering why you worked so hard for so little.

In the real world, if you're lucky, you either play nice with others, or find yourself suddenly unemployed. If you aren't so lucky, your employer doesn't care if you smell like sweat socks and annoy your colleagues with conspiracy theories, because basically they don't even care if you are a carbon-based life form, as long as you crank out code.This type of employer treats you like a replaceable part, and discards you like last years' cell phone when they're done with you.

In the real world, your CEO is probably not a geek. He's probably an extraverted, glad-handing, back-slapping, ex-frat-rat, because weirdly enough that's the right skill set for a CEO. He definitely votes Republican. And he thinks you look a lot like the nerdy kids he used to stuff into lockers and trip in the cafeteria.

Working in the real world is a job. It can be a lot of fun, but it's also a lot of work, and a certain amount of tedium, and a certain amount of putting up with stuff you don't like. There are 2,000 Mondays in the average career. Anyone who tells you different doesn't know what he's talking about.

There's this place called Xerox PARC. At the dawn of the Computer Age they invented personal computers, and Ethernet, and Smalltalk, and windows and stuff. And the conference rooms were full of beanbag chairs and the streets were paved with gold. This is what your professors think the real world looks like.

|

| Xerox PARC, ca. 1980: A fantasy of the real world |

This is the "real world" you hear about in college. It's a world where nerds rule and employers are so desparate for top talent that they'll do anything to keep you happy.

It's a fantasy; a fairy tale told by people (students) who have never even seen the real world, and people (professors) who turned their backs on the real world in favor of a place where you could never ever ever be fired no matter how you behaved, once you got tenure.

Mostly, the real world looks like this.

|

| Sorry, this is a lot more real |

Employers really are desparate for top talent. Only the thing is, new grads aren't top talent, no matter how smart you are. You're a n00b, a novice. You won't even know how much you don't know for a couple of years. To employers, top talent means that one guy on the team who turns out 10 times as many lines of solid, functioning code as anyone else; who works 80 hour weeks for 40 hours of pay; who's been coding since he built his first computer from individual logic gates when he was six. Top talent has already worked for Microsoft and Google and Facebook. That's how your employer knows they're top talent. You haven't worked for anyone at all.

There are indeed startups with free food, and wine, and foosball, and a fancy office. They just aren't all the same startup. And most of them are in just one or two cities; cities where a decent house costs a million bucks; cities you don't currently live in. What every startup has is long hours and low wages and stock options, which 99 times out of 100 expire worthless, and 1 percent of the time make you a millionaire. Most startups only live for a year. Then they crash and take your dreams of wealth with them, leaving you unemployed, wondering why you worked so hard for so little.

In the real world, if you're lucky, you either play nice with others, or find yourself suddenly unemployed. If you aren't so lucky, your employer doesn't care if you smell like sweat socks and annoy your colleagues with conspiracy theories, because basically they don't even care if you are a carbon-based life form, as long as you crank out code.This type of employer treats you like a replaceable part, and discards you like last years' cell phone when they're done with you.

In the real world, your CEO is probably not a geek. He's probably an extraverted, glad-handing, back-slapping, ex-frat-rat, because weirdly enough that's the right skill set for a CEO. He definitely votes Republican. And he thinks you look a lot like the nerdy kids he used to stuff into lockers and trip in the cafeteria.

Working in the real world is a job. It can be a lot of fun, but it's also a lot of work, and a certain amount of tedium, and a certain amount of putting up with stuff you don't like. There are 2,000 Mondays in the average career. Anyone who tells you different doesn't know what he's talking about.

Thursday, July 21, 2011

The Dream Team (a Management Anti-Pattern)

Senior developers are more productive than junior ones, or so I tell myself. Still, most employers like to hire devs 2-5 years out of college. Managers say, "These guys ae still fresh, with up-to-date skills, but they've learned how to work." But what managers think is, "These guys are cheap, and they do what they're told, because they don't have a lot of independent experience giving them ideas that conflict with my judgements."

But that's not what I would do. If I ran the world, I'd hire devs with 10+ years experience; devs who already knew what to do and could go do it without supervision. Some startups work like that. Yeah, an Old Hand costs more, maybe twice as much as raw rookies right out of school, but they are way more productive. They only have to be twice as productive (counting the managers you don't have to hire), to make them pay off.

I took a job at a company like that once. They bragged that they only hired senior folks. And indeed, the staff, taken as individuals, were bright and talented and very experienced. I was very excited, because this was just what I would do. I thought I was joining a dream team. Reality was quite a let-down.

The company founder was a guy who liked to code very fast. In fact, he'd hired this team to clean up after him. Over time the team became so outraged by the poor quality of the founder's work that they chased him away to "other opportunities". Problem was, people like to hire themselves, and the founder had hired a staff that liked to write code quickly, but didn't care to do that other stuff, like documentation, coordination, testing, etc.

One very senior C++ developer didn't trust objects. Their code looked like C, and had all the problems of C code. Another one had a very idiosyncratic coding style; they put all their method definitions in the header file. Partly this was a bad java habit. Partly they used a third-party tool for indexing the sources that worked better when the declarations and definitions were all in the same place (I think, sort of. I still don't understand). Another had a bunch of antiquated style habits they'd picked up in 1995, and couldn't imagine how their practice could possibly improve by changing their style to use modern features of C++. Naturally they each had their own indentation style, their own variable-naming conventions, and pretty much every other thing that they could do differently, they did.

They'd broken the code up into fiefdoms, so they weren't exposed to the silly habits of their peers. And they defended these fiefdoms fiercely. One of them checked in a change to my code because I'd started a one-line comment with "//", when they preferred "/* ... */". Whatever, man.

Each fiefdom had their own include files, with duplicates of the same basic stuff, that had aged differently. The code base frequently produced compile warnings (on error level 3 in Visual Studio). They didn't lint the code, or use error level 4 because it produced too many error messages, and some devs would have to change their styles to make these go away. In fact, we had a critical bug delay a release, that turned out to have printed a compiler warning. Only there were so many warnings that nobody noticed this one, or bothered to follow it down into another dev's fiefdom and fix it.

They used a funky build tool written in python, rather than build inside Visual Studio or use make. Only two of the devs knew how to fiddle the build tool. They fought with each other endlessly, changing things back and forth.

They didn't really have any documentation for their creaky old code base. When I started doing docs, it started a war. One dev thought documentation should go into a wiki. Another thought it should be static HTML web pages. One thought Word was ok. Another thought we'd be more productive in FrameMaker (which is true, but FM is expensive). One wanted docs in the source code. Another argued that no documentation could be trusted because sometimes it might be out of date, so we shouldn't even comment the code.

We bickered about whether to put the docs in the source tree, or in one of two different styles of separate file tree. I tried to suggest that the first and only really important thing we should argue about was, what aspects of the project were most important to document, and worry about how to type it later. They thought that was crazy-talk. Each used the war as justification for not documenting their code.

An Old Hand reading this may have guessed by now that the problem was management. The lead was not doing anything to make the team work together as a team. By the time I got there, it was probably too late to change them anyway.

This company was a ten-year-old startup (which is an anti-pattern itself). Their product was pretty cool, but they were having trouble breaking out into the big time. The code had a million features, and a million little bugs. They knew they needed to work on improving their robustness because the next set of customers they had their sights on were big enough to demand really solid reliability. But the siren-song of each next customer was filling up the work queue with new feature requests.

I only made it six months at that company. They thought I should go, and I agreed. The feeling I had when I left must have been like viewing the Titanic from the perspective of the last lifeboat to pull away. Only the guys aboard the Titanic knew the ship was sinking.

Teams make the company. Not individual performers, no matter how experienced, talented, or bright they are. The Dream Team of individual performers is a management anti-pattern unless they are in fact managed as a team.

But that's not what I would do. If I ran the world, I'd hire devs with 10+ years experience; devs who already knew what to do and could go do it without supervision. Some startups work like that. Yeah, an Old Hand costs more, maybe twice as much as raw rookies right out of school, but they are way more productive. They only have to be twice as productive (counting the managers you don't have to hire), to make them pay off.

I took a job at a company like that once. They bragged that they only hired senior folks. And indeed, the staff, taken as individuals, were bright and talented and very experienced. I was very excited, because this was just what I would do. I thought I was joining a dream team. Reality was quite a let-down.

The company founder was a guy who liked to code very fast. In fact, he'd hired this team to clean up after him. Over time the team became so outraged by the poor quality of the founder's work that they chased him away to "other opportunities". Problem was, people like to hire themselves, and the founder had hired a staff that liked to write code quickly, but didn't care to do that other stuff, like documentation, coordination, testing, etc.

One very senior C++ developer didn't trust objects. Their code looked like C, and had all the problems of C code. Another one had a very idiosyncratic coding style; they put all their method definitions in the header file. Partly this was a bad java habit. Partly they used a third-party tool for indexing the sources that worked better when the declarations and definitions were all in the same place (I think, sort of. I still don't understand). Another had a bunch of antiquated style habits they'd picked up in 1995, and couldn't imagine how their practice could possibly improve by changing their style to use modern features of C++. Naturally they each had their own indentation style, their own variable-naming conventions, and pretty much every other thing that they could do differently, they did.

They'd broken the code up into fiefdoms, so they weren't exposed to the silly habits of their peers. And they defended these fiefdoms fiercely. One of them checked in a change to my code because I'd started a one-line comment with "//", when they preferred "/* ... */". Whatever, man.

Each fiefdom had their own include files, with duplicates of the same basic stuff, that had aged differently. The code base frequently produced compile warnings (on error level 3 in Visual Studio). They didn't lint the code, or use error level 4 because it produced too many error messages, and some devs would have to change their styles to make these go away. In fact, we had a critical bug delay a release, that turned out to have printed a compiler warning. Only there were so many warnings that nobody noticed this one, or bothered to follow it down into another dev's fiefdom and fix it.

They used a funky build tool written in python, rather than build inside Visual Studio or use make. Only two of the devs knew how to fiddle the build tool. They fought with each other endlessly, changing things back and forth.

They didn't really have any documentation for their creaky old code base. When I started doing docs, it started a war. One dev thought documentation should go into a wiki. Another thought it should be static HTML web pages. One thought Word was ok. Another thought we'd be more productive in FrameMaker (which is true, but FM is expensive). One wanted docs in the source code. Another argued that no documentation could be trusted because sometimes it might be out of date, so we shouldn't even comment the code.

We bickered about whether to put the docs in the source tree, or in one of two different styles of separate file tree. I tried to suggest that the first and only really important thing we should argue about was, what aspects of the project were most important to document, and worry about how to type it later. They thought that was crazy-talk. Each used the war as justification for not documenting their code.

An Old Hand reading this may have guessed by now that the problem was management. The lead was not doing anything to make the team work together as a team. By the time I got there, it was probably too late to change them anyway.

This company was a ten-year-old startup (which is an anti-pattern itself). Their product was pretty cool, but they were having trouble breaking out into the big time. The code had a million features, and a million little bugs. They knew they needed to work on improving their robustness because the next set of customers they had their sights on were big enough to demand really solid reliability. But the siren-song of each next customer was filling up the work queue with new feature requests.

I only made it six months at that company. They thought I should go, and I agreed. The feeling I had when I left must have been like viewing the Titanic from the perspective of the last lifeboat to pull away. Only the guys aboard the Titanic knew the ship was sinking.

Teams make the company. Not individual performers, no matter how experienced, talented, or bright they are. The Dream Team of individual performers is a management anti-pattern unless they are in fact managed as a team.

Tuesday, June 21, 2011

Other, Younger Old Hands

I just came across this on StackExchange. Another Old Hand, this one only 32, laying down her rules of life in case they proved valuable.

The Developer's <code>

The Developer's <code>

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)